It had been over 1,000 years since the god Apollo had descended from Mt. Olympus. He was tired. As each century passed, he had grown weaker and weaker without followers. Or, at least he felt weaker. Though he still ate the ambrosia and drank the nectar, he didn’t feel like getting out of bed with the knowledge that no one would pray to him for inspiration and Delphi would only house unbelieving tourists. His muscles felt hollow and his head felt empty. Sometimes, when Hermes and Zeus weren’t looking, he would try to cry, to scream, to experience the catharsis that had been his job to bring to mortals, but nothing came. Nothing at all. Nothing! He hadn’t known what was wrong for a very long time. He had had nothing to do but play in the fields and strum on his lyre but, try as he might, there had been nothing to compose. Nothing for him to play on his lyre but the old tunes, tunes that grew more and more drab with each passing day. He had sometimes wished himself mortal so he could die, but quickly dismissed the thought. He was a god! Above all mortals! Forever and ever he would reign! Amusedly at first, he decided to check on the state of art in the mortal world. His powers had faded a bit, but he could still watch and listen rather easily.

In his sessions, he found beat and sorrow, breath in song, strange ivory contraptions. The paintings were moving away from showing the human form as it was and towards showing the human form as it was imagined. And the tales were downright absurd. There were still heroes, sure, but they were crippled by shortcomings and rose above anyway. And no gods! These poor mortals. So confused they were. He’d show them.

He waited.

He had expected the mortals to feel his engagement, to become aware he was back and resume praying to him, but they didn’t. Oh, well, it was still fun to watch. As he only observed the art, he could only see the echoes of what was real, but he began to suspect something had happened to the mortals. Something big. Then, slowly, among the bards and players, heroes emerged. Great poets and actors, gracing our world. Even those people who were only living canvases got more attention than Apollo did. It was that bard that infuriated him the most–the one with the fast rhythms and even faster hips. Everyone loved him, worshiped him. But they had completely forgotten about Apollo. The more it went on, the more his heart ached and cracked. Oh, he would give anything to hear the crowds cheering his name. Briefly, he had thought about breaking up a group of bards just for the fun of it, but he had forgotten that they were mortals–petty, selfish beings overly concerned with their drama﹘ and they broke themselves up soon enough. Besides, what he really needed wasn’t to hurt them, it was to help himself. He was still the god of the arts; so what if his domain had never stretched past the Aegean and he hadn’t had a follower in thousands of years? He would get their eyes back on him no matter what. There was another mortal–they popped up all the time. And while they were fresh, they were vulnerable. They knew they were liable to run out of ideas. He would help this one. In return, he would only ask for a little bit of worship. He knew it was unbecoming of a god to hitch himself to a mortal, but desperate times called for desperate measures.

Hence, Apollo floated on a wind over the sea. He found himself faltering over the Aegean, but he managed to reroute to Egypt and find an Apis bull as a guide. When Apis collapsed, Apollo skirted from paintings’ origins to the places they hung. Thus, he made it to London. From there, all he had to do was sit comfortably on a song as it went from London to New York. Across the United States he journeyed this way, paying no mind to the battered gods as old as Turtle Island itself. He could only afford to look out for Apollo, after all. He was everywhere now; he had picked a good song. What a strange ballad it was–the Earth was ending! But no, in real life, nothing died. Not the gods, not their reign. Nothing. He dawdled a bit in bacchic excess, and then came to his target.

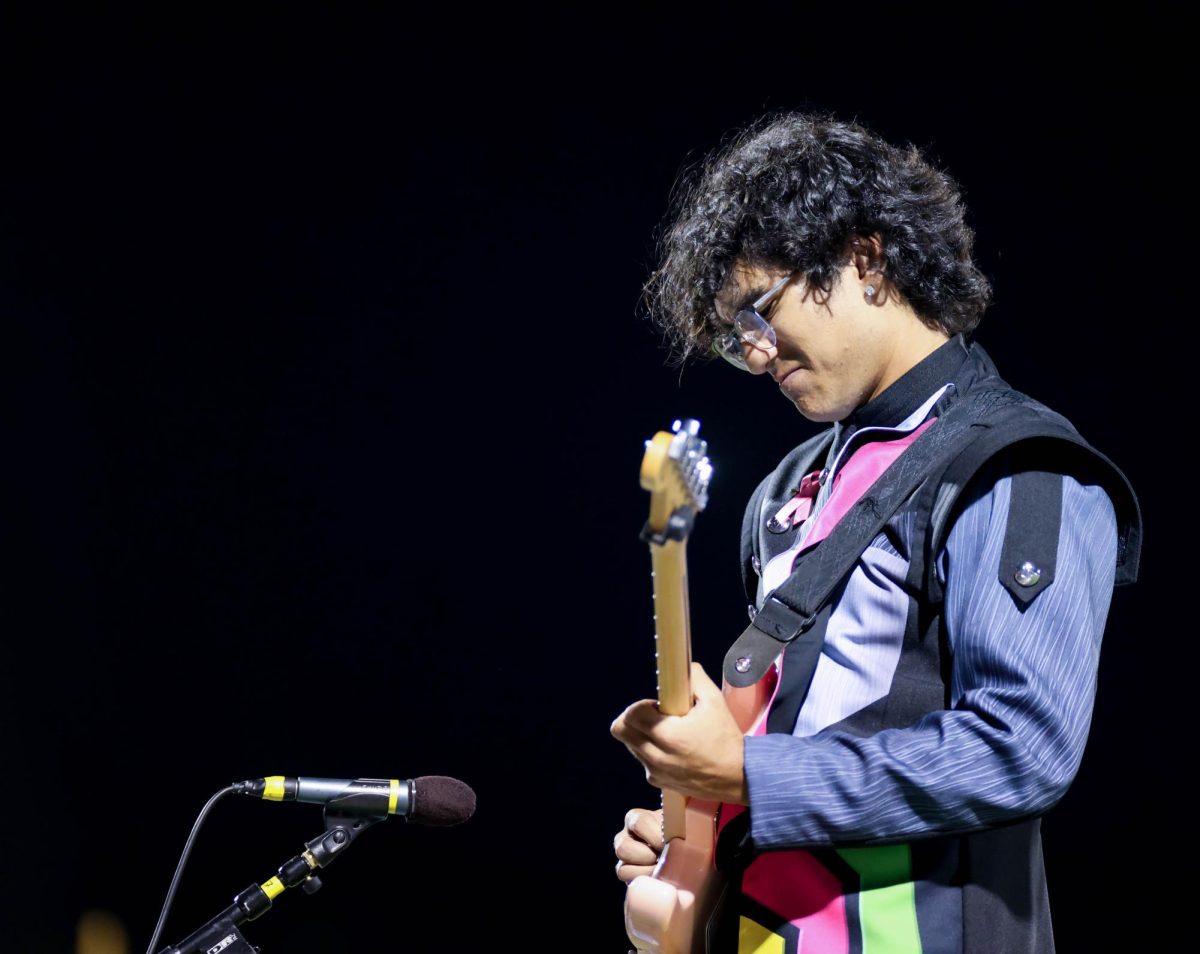

In a brilliant flash of light on that rock star’s momentarily-favorite track, Apollo burst forth, his golden hair and eyes shimmering just enough to inspire awe, a sun-styled crown upon his head, a tunic of shining lights of sun and stage adorning his body, and sandals of the softest leather on his feet. He looked down at the Rockstar, dressed in flared pants and a colorful rayon shirt, who was sitting cross-legged on the floor with lyrics sheets surrounding him. The Rockstar looked up at Apollo with the curiosity of an owl, taking a drag off of his cigarette.

“So,” the god Apollo said to the Rockstar, “I’ve heard you’ve had some success.”

“Yes,” the Rockstar replied casually, “I’m really proud.” And then, as an afterthought, “Who are you?”

Apollo blinked. This wasn’t how it was supposed to go. With all the bravado he could muster and an extra burst of celestial sunlight, the god Apollo cried, “I am Apollo, God of the Arts, God of the Sun, God of Marksmanship, God of Sickness and Health. I am the voice behind the oracle at Delphi. I am the one who cursed Cassandra! I am the one who… is any of this ringing a bell?”

“Oh, yes, I know who you are,” the Rockstar replied, nodding, “I was waiting for you to finish.”

“But…you didn’t react at all.”

“Oh, um, well, that’s far out, being all those things, isn’t it?” The Rockstar smiled. He pushed a tuft of his fluffy hair behind his ear.

“Yes, um, it is,” Apollo replied, not hiding his irritation. Of course it was “far out” to be a god. Why, he was up above and mortals were down below. He was far and away from all the comings and goings of mortal life.

“Well, good for you,” said the Rockstar. Apollo blinked again. He’d just have to move on.

“Um, okay,” Apollo said, “About you… um, that was just one album. I’ve had some success in my day, too. In fact, I was literally worshipped.” Apollo felt he should be selling himself more, but he wasn’t sure how to get this mortal to look at him with the awe the Greeks would look at him with just for being there. The way they’d look when they’d just think about him. He hadn’t really had to win the respect of those mortals. Zeus had given him the arts, health, even the sun. Those credentials had done the talking for him. The placid way the Rockstar was sitting and nodding and smoking baffled Apollo to no end.

“Anyway,” Apollo continued, “Yeah, just one album. I can tell you– losing relevance is like dying, I assume. I want to get my relevance back, and you want to stay relevant, don’t you?”

“I guess so,” the Rockstar took another drag off the cancer stick.

Apollo snatched the cigarette out of his mouth.

The Rockstar looked offended, but at least he seemed more focused on Apollo.

“Look, I’m offering you ideas!” Apollo shouted. He could feel his glow getting hotter. “Ideas for songs, books, paintings, whatever you want! For the rest of your miserable life! In return, all I ask is that you give me credit. That you say the Great God Apollo inspired you.

“They’d think I was a heathen or something.” The Rockstar shrugged.

“Well, I’m here, aren’t I? I’m talking to you, aren’t I?” Apollo raged.

“I guess you are,” the Rockstar said, laughing, “Look, I’m not trying to be ungrateful. This is really a very neat experience for me. Almost as great as 2001. Have you seen 2001?”

“No, but I’m sure it pales in comparison to what I can give you!”

“Oh, okay. Well, um, this is awkward, but I’m just gonna have to say thank you very much for the offer, but I’d like to pass. I’d really rather just keep doing this on my own.”

Flames erupted all over the god’s skin.

“WHAT?!”

“I said,” the Rockstar replied evenly, “I’d rather keep doing this on my own.”

“But I– listen, you’re the first mortal I’ve given this kind of offer to. I used to give mortals inspiration all the time, sure, but after they asked. You’re the first person in history that I’ve just… offered it to.” Apollo was put out.

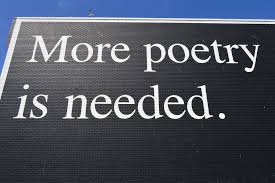

“Well, again, thank you,” the Rockstar replied kindly, “I truly am very flattered and thank you very much for coming from wherever you came from. For coming down—,” he chuckled a little, “—or up or sideways. But, you see, the problem is that I write for myself. Just for me. And, if I had you inspiring me, I wouldn’t be writing anymore. And then, what’s the point of performing or anything? There’d be no fun in it.”

Apollo seethed. What was wrong with this mortal? Didn’t he want to ensure his relevance? His place in history? Wouldn’t he give up anything for it? It’s what Apollo would do. What was this about art for the fun of it? Shouldn’t he be concerned about rising above mortals? Didn’t he want to touch the cuff of the gods? Maybe Apollo could say something to snap him out of it, let him know that mortal art was all of the same base matter. Yes, a clever insult. The kind that makes you stop and think. He had it!

“Well, have fun lifting melodies off of movie tracks!” Apollo stage-shouted.

“Hey, wait a minute!” The Rockstar was genuinely irritated now, “That’s what it’s all about, lifting melodies off of movie tracks. It’s about that human connection and experience, so if we use something someone else has already made, then that’s sort of like building a new community. Saying, ‘I know it and you know it.’ And maybe it works because we’re all living in this crazy and strange and dark and light world and we all have different ways of looking at it and of seeing it, but sometimes they intersect, maybe a little or maybe a lot… and then they might branch off again!” He was beaming at the thought of it. He continued, “So if we want to use something someone else made and take it off in a new direction, that’s art! We’re trying to communicate with other human beings, shout into the void and ask, ‘Is anybody there?’ If that’s the best way to communicate, well that’s all well and good because it’s about the connection. It’s just what human beings do. In fact, what kind of art would a god make anyway? How would humans listen to it, watch it, read it? What would they think? Would we find it’s supposed to be listened to with our feet? I don’t know. It’s like- it’s like how a computer can’t make art ‘cause it’s got no soul.”

“Well, I could make it just like mortal art!” Apollo screeched, “I could model it after mortal art. Produce what a mortal would make!” He knew he was lowering himself with the offer, but if that was what art was, somehow. Or, he figured, if that’s what this man thought it was. And he needed to convince this man to help him.

“That’s even worse!” The Rockstar shouted. “In fact, that’s the most disgusting thing I’ve ever heard!”

“But you just said using other people’s stuff was okay!” Apollo cried frustratedly.

“For the purposes of communicating and referencing and going off and making something new, sure, but when it’s done with a human intent and a human vision. A human idea. It is not for pumping out some crap you think people will like.”

“So, that’s it?” Apollo screamed. “You’re just gonna refuse my help? You’re just gonna keep doing this forever?”

“Oh, no,” the Rockstar replied, smiling, “I’ll do whatever I want! Most people don’t get this kinda opportunity. I’m gonna use it to keep singing and writing and playing forever, sure, but singing and writing and playing what I want with who I want to work with!”

“But people love what you’re doing NOW!! People love who you are NOW!!!”

“No, they love the connection. Why do you think I started with this? ‘Cause I was bored of what I was doing before!” The Rockstar laughed. “I do hope people keep making new stuff after me. I hope in 50 years, there’s still something new to listen to.”

“But, but, you, I-” Apollo’s mouth twitched, but no words came out.