Our tour guide in Belfast, Northern Ireland informed us that curfew was 11 p.m. and the gates would shut at that time. The gates were more symbolic than anything, but they had once served as a physical barrier between the two sides of the Protestant and Catholic controversy in the 70s and 90s. Riot barricades and 20-foot-high walls began at nearly every neighborhood block and were covered in decades-old graffiti and political murals. Belfast was now peaceful and even our tour guide Mark, who had grown up in the middle of this religious war, felt safe in his home for the first time. However, the city served as a post-industrial, permanent reminder of what religious warfare does to a country’s progression and the community that resides there. Mark walked us through the tragic history, the current climate, and the real-world applications of the English Protestant and Irish Catholic “Troubles” that shook the world and are still present today in other forms.

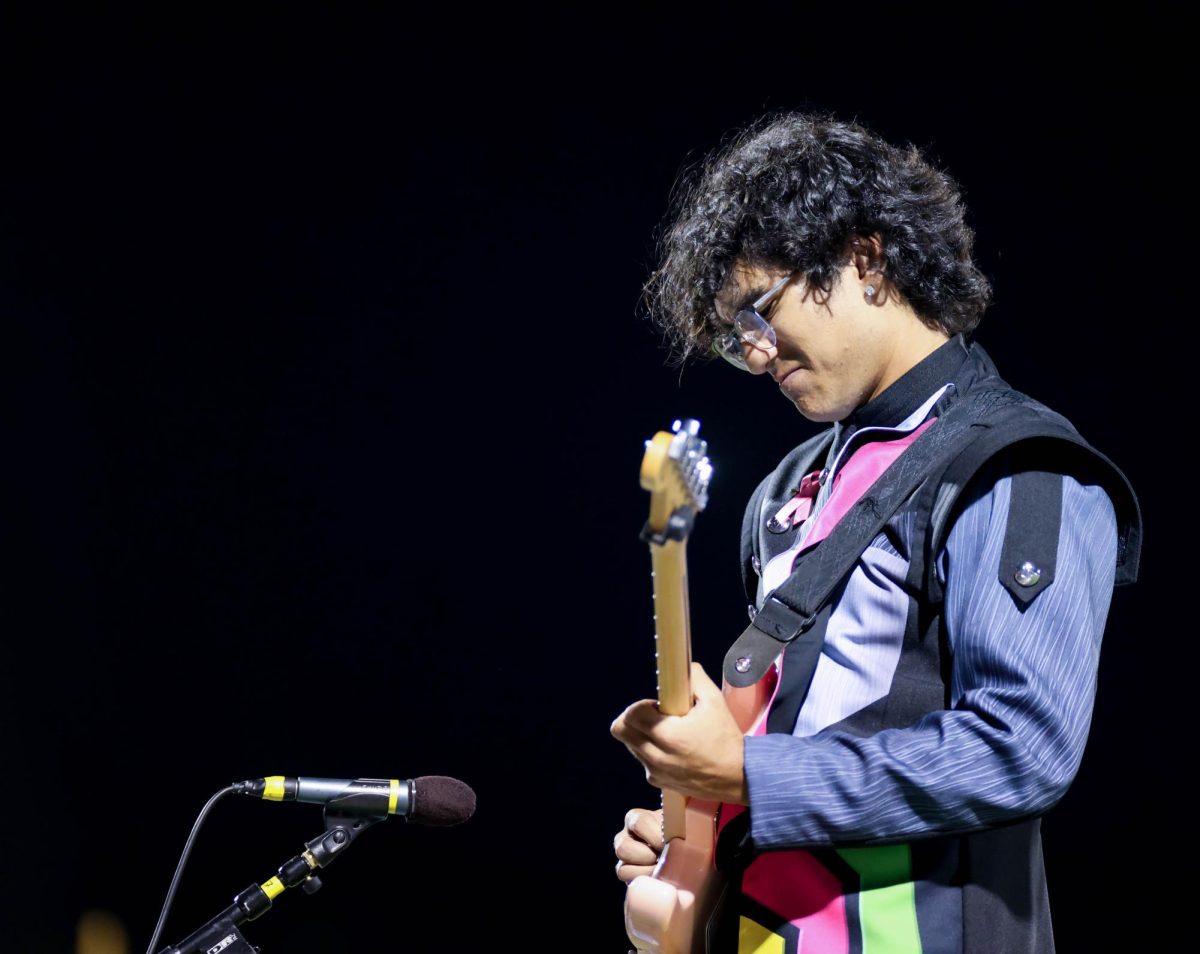

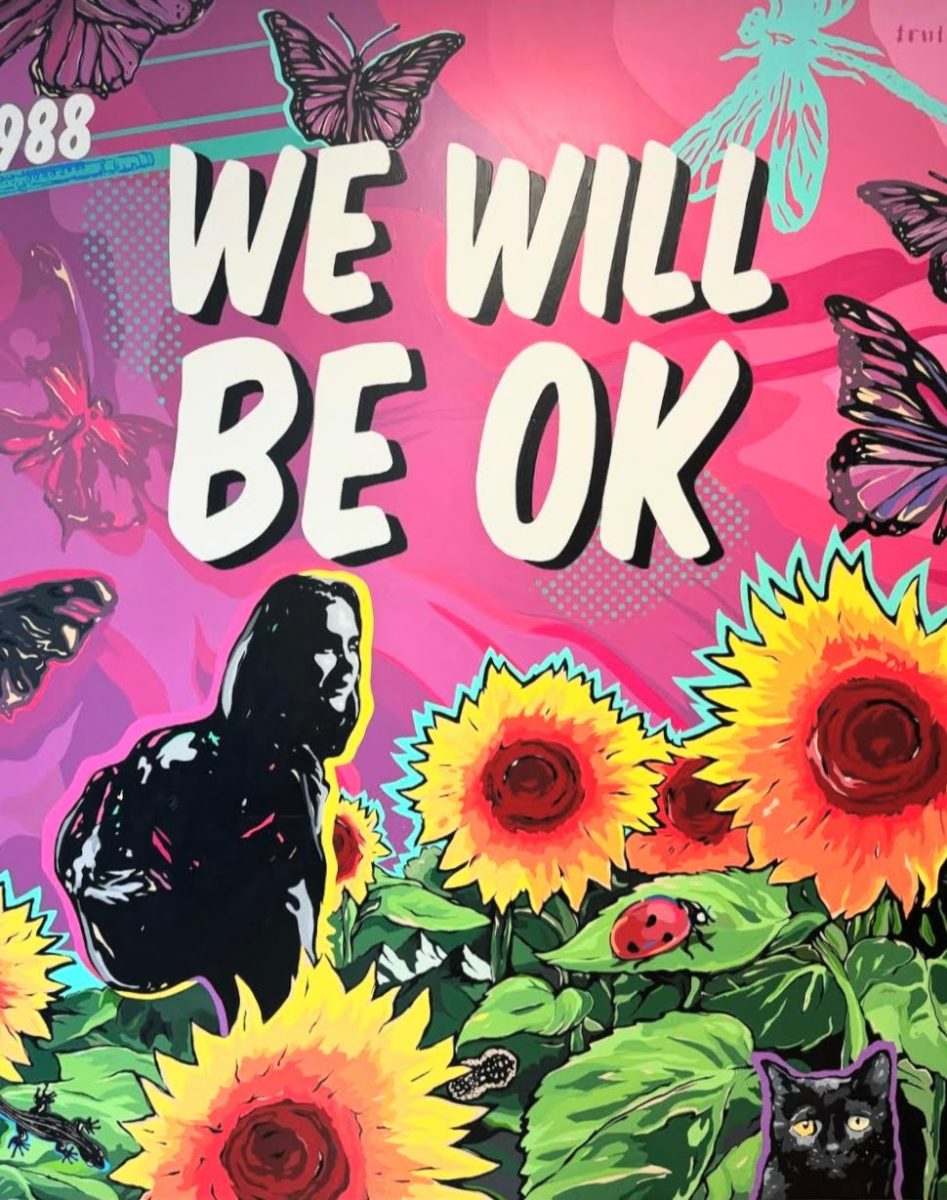

The controversy is deep-rooted in the United Kingdom’s politics, dating back to the 16th century Reformation, when England’s King Henry VIII separated from the Catholic Church, and Ireland’s Catholic majority resisted English Protestant dominance. This led to Catholic oppression and the Republic of Ireland declaring its independence in 1921. Religion has defined the borders of Northern Ireland, The Republic of Ireland, and their relationship with England since Ireland’s inception. These countries witnessed a resurgence of violence in 1968 when Northern Ireland, composed of mostly Catholics, sought reunification with the Republic of Ireland. Protestants, living in Northern Ireland, who wished to remain part of the United Kingdom refused to cooperate in this effort. The question of whether to rejoin the United Kingdom boiled down to historical religious loyalty. Belfast was the greatest hotspot where the atrocities for religious freedom were committed on both sides. Our tour guide, Mark, once again explained that “The Troubles” surrounded the question of which religion was the rightful “owner” of the lands, and therefore which side should control the future and loyalties of the country. Catholics sought their own Ireland, separate from their oppressors in England, whereas Protestants, coming to the country after the Catholics, believed that Ireland had been conquered, and was to rejoin the UK as a whole. The violence that followed stemmed from paramilitary groups and bombings resulting in thousands of deaths and injuries. Walls were erected around the city to mitigate Catholic residents’ contact with Protestants and vice versa. Curfew was enacted, and these were just the beginning of political remedies that are still around today. Political murals cover the streets and sides of houses and serve as a constant reminder that “Lest We Forget” (a statement painted on many murals), thousands of people may be killed again simply for their loyalty to a religion, country, or belief.

The message became clear; both sides were fighting for what they believed was true freedom. While the topic and history of this conflict deserve more discussion, some of the most interesting information I learned included the parallels between the Catholic and Protestant conflict and the Israel and Palestine war. In this case, the world seems to be forgetting the consequences of religious hatred along borders, as war wages on in Israel over the parallel conflict of Zionism. The similarities between the conflicts are staggering. Similarly to Ireland, Palestine has a deep-rooted and complicated relationship with England. On November 29, 1947, the Partition Resolution divided Great Britain’s former Palestinian mandate into Jewish and Arab states in May 1948. The partition ended British rule and left these two warring ‘stateless nations’ to build their government and continue the war over the “rightful control” of the holy lands located in Israel. Palestine, which originally occupied the land that Israel now governs practiced Islam, and Israel, Judaism. These two Abrahamic religions hold religious significance in the holy lands of Jerusalem. The British partition sought to end tensions between Judaism and Islam but conversely heightened them by dictating which religion warranted political autonomy. Palestine currently wishes to reclaim its historic land, much like Catholics wished to remain autonomous over Ireland from 1960 to 1998. Israel, like that of England in unifying the United Kingdom, seeks to unify the eastern Mediterranean region. The same violence is also prevalent in the area, and this has alerted Ireland to the severity of this controversy. Hunger strikes and bombings, like the ones that happened in Northern Ireland, are being repeated in Israel by Palestinians. People around the world worry for the lives of these religious protesters, but the people of Ireland understand and support them in solidarity.

In Catholic neighborhoods in Belfast, Irish residents fly Palestinian flags whereas, conversely, Protestant residents fly Israeli flags to show their support. The undertones of “rightful ownership” will never fully dissipate as current events mirror the history of Northern Ireland. However, these people will never forget their loved ones that perished. In addition, Mark shared that he is hopeful for the next generation of Irish children. He said that kids know the world is bigger than the city blocks of Belfast. They know peace is an option that didn’t seem available to the children of the crossfire. He hopes violence will not be resorted to on all occasions, which, unfortunately, is happening in the case of Israel v.s. Palestine. He stated that in this context, he hopes for this controversy to be handled better, and with peace as the focal point. Lest we forget all those who have died fighting for their religion and their country, we will witness history repeating: the message of this politically charged summer in Belfast. Will the remembrance of “The Troubles” bring peace to Palestine and Israel? Northern Ireland prays for peace nightly when their street gates close for curfew.